Patients

-

- Angiography

- Angioplasty and Stenting

- Aortic Aneurysms

- Biliary Drainage and Stenting

- Carotid Artery Stenting

- Central Venous Access

- Colonic Stenting

- Fibroids

- Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage

- Gastrostomy

- Hepatic Malignancies

- Kidney Tumour Ablation

- Minimally Invasive Treatments for Vascular Disease

- Nephrostomy

- Oesophageal Stents

- Pelvic Venous Congestion Syndrome

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

- Prostate Artery Embolisation PAE

- Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations

- PAE Patient Information Leaflet

- Ureteric Stenting

- Varicoceles

- Varicose Veins

- Vascular Malformations

- Vertebral Compression Fractures

- Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty

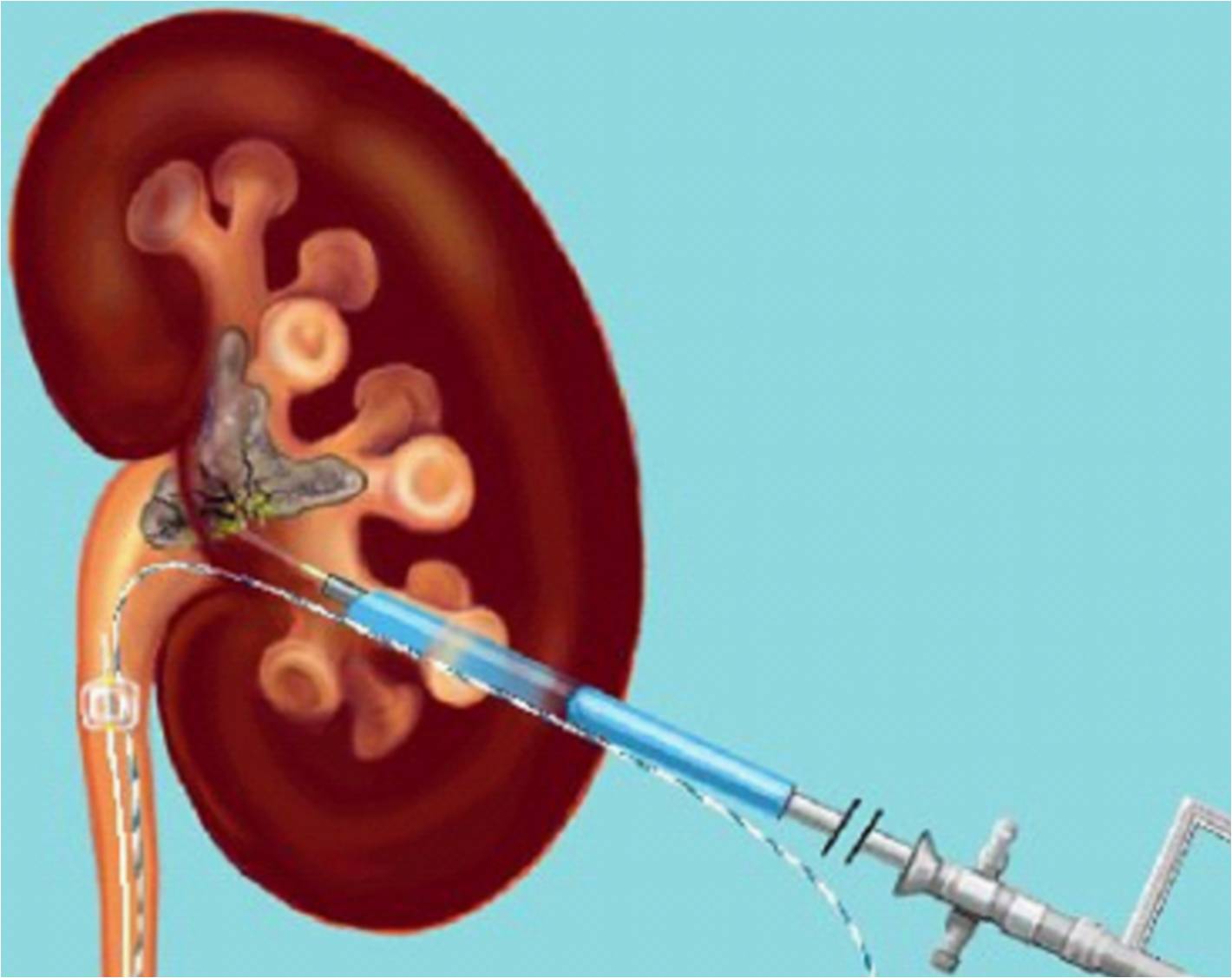

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

Content by Dr Sivanathan Chandramohan, Consultant Interventional Radiologist, Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow.

What is Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy?

Removal of kidney stones using keyhole surgery.

What are kidney stones and why do I get them?

Kidney stones are a common problem affecting anyone irrespective of geographical, cultural or racial differences.1

Approximately 14% of men and 6% of women will develop a stone disease during their lifetime 2,3. Recurrence rates for stones are 50% within 5-10 years and 70% within 20 years. There are various factors which contribute to the formation of renal stones which include familial, environmental, dietary and due to some systemic diseases.

Are there differences between stone types?

The types or classification depend upon the location of the stones, size of the stones, composition of the stones and density of the stones. Taking all these factors into consideration, a management plan is devised.

Can kidney stones be prevented?

There are a few diets associated with increased risk of stone formation and restricting their usage will help to some extent. Generally reducing amount of protein and salt intake will help.4 Taking plenty of fluid will also reduce the recurrence rate of stone formation.

How are kidney stones diagnosed?

Kidney stones are diagnosed mainly by three types of imaging. X-rays and ultrasound scans can show the kidneys stones but now it is very common to perform a CT scan to diagnose stones in the kidney. Of the three, CT scans are very good (more sensitive) in picking up stones in the kidney or the structures which drain the urine from the kidney into the bladder (ureter).

Are there any other treatment options?

- Removal of stones using open surgery

- External shock-wave treatment

- Simple observation.

Open surgery involves a larger cut in the back where the kidneys are and this is rarely performed e.g. when PCNL and other methods to remove the stones fail. The external shock-wave treatment (extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy ) is used for stones of less then 1cm in the kidney or in the proximal ureter. Other treatment option involves a camera from below through the bladder into the ureter called ureteroscopy which can be used to treat the stones in the ureter and stones which are less than 1cm in the kidney. This allows visualisation of the stones and fragmenting them using a laser before removing them.

When is PCNL performed (indications for PCNL)

- Stones larger than 1.5cm in the kidneys or the ureter.

- Stones larger than 1cm in the lower pole of the kidney.

- Staghorn shaped stones.

- Patient choice

How is the procedure done?

Usually you will be admitted on the day of the surgery unless you have any other risk factors. One of the urology team members will see you before the procedure to confirm or obtain consent for the procedure. The procedure is normally performed under general anaesthesia therefore you will be completely asleep throughout the procedure. A fine bore tube is passed from below using an endoscope (cystoscope) into the kidney through your bladder. Then you will be placed on your tummy and the skin over the kidney area will be cleaned using an antiseptic solution. Using xray and/ or ultrasound guidance, a wire will be passed into your kidney where the stone is. Then a 1cm cut is made in the back and a temporary rigid tube is placed from the skin onto the kidney which will be removed after the surgery. Then a camera (nephroscope) is used to visualise the stone which will then be subsequently fragmented and extracted. Sometimes, if the stone burden is higher, you may have two or three incisions to access the kidney to ensure complete stone clearance.

What happens after the procedure?

Usually, there will be a tube left in the kidney post procedure to drain it. You will also have a urinary catheter left in the bladder. The following day, an x-ray will be performed to check for any residual stone left in the kidney. You may also have an X-ray dye test through the drainage tube from the kidney, one or two days post procedure. If this test is satisfactory, then the tube will be removed. Expect to stay in the hospital for 4-5 days.

What are the complications?

As with any invasive procedure, there are some complications associated with the procedure but the chance of this happening is small.

Common or frequently occurring complications or side effects are transient blood in the urine and raised temperature. These will settle within a few days. Occasionally, you will get severe bleeding which requires a blood transfusion and/ or embolisation (blockage of blood vessel supplying the kidney). As a last resort, you may have a surgical removal of the kidney if the bleeding is severe. As the kidney is closely related to other structures, rarely there can be damaged as well. The organs close to the kidney like bowel, spleen, liver and lung can be damaged which might require further surgical intervention. Over-absorption of irrigating fluids during the procedure into the blood system can cause strain on the heart function 5.

Please note that there is no guarantee of removal of all the stones in one sitting and you may require additional treatments. Failure to establish access into the kidney may result in further treatment.

How much does it cost?

In a private hospital the procedure will cost approximately £5500.

References

- Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet 2006;367(9507):333–344.

- Pak CY. Kidney stones. Lancet 1998;351(9118): 1797–1801.

- Soucie JM, Thun MJ, Coates RJ, McClellan W, Austin H. Demographic and geographic variability of kidney stones in the United States. Kidney Int 1994;46(3):893–899.

- http://www.baus.org.uk/Resources/BAUS/Documents/PDF%20Documents/Patient%20information/Stone_diet.pdf

- http://www.baus.org.uk/Resources/BAUS/Documents/PDF%20Documents/Patient%20information/PCNL.pdf