Patients

-

- Angiography

- Angioplasty and Stenting

- Aortic Aneurysms

- Biliary Drainage and Stenting

- Carotid Artery Stenting

- Central Venous Access

- Colonic Stenting

- Fibroids

- Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage

- Gastrostomy

- Hepatic Malignancies

- Kidney Tumour Ablation

- Minimally Invasive Treatments for Vascular Disease

- Nephrostomy

- Oesophageal Stents

- Pelvic Venous Congestion Syndrome

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

- Prostate Artery Embolisation PAE

- Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations

- PAE Patient Information Leaflet

- Ureteric Stenting

- Varicoceles

- Varicose Veins

- Vascular Malformations

- Vertebral Compression Fractures

- Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty

Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage

Content by Dr Dinuke Warakaulle, Interventional Radiologist, Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Aylesbury

What is Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage?

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage (GIH) is bleeding that occurs from the digestive tract. This can be a slow loss of small volumes of blood, or a sudden massive loss of blood requiring urgent treatment. This section concentrates on the latter, and aims to inform readers about Radiological options for diagnosis and treatment.

Who gets GIH?

GIH can happen to anyone, of any age, but tends to occur mainly in elderly people.

What are the causes of GIH?

GIH can be due to a wide variety of causes, including ulcers, tumours, abnormal blood vessels (eg. angiodysplasia), blood clotting disorders, or after trauma or surgery.

What are the symptoms of GIH?

The symptoms depend mainly on the location of the bleeding point in the digestive tract and the rate of bleeding.

Bleeding from the upper digestive tract (stomach, small intestine and large bowel closest to the small bowel) can present with vomiting blood, or passing melena (dark, tarry, offensive stool due to blood that has been altered during passage through the digestive tract). Rapid bleeding can lead to the passing of dark or bright red blood from the rectum.

Bleeding from the lower digestive tract (remainder of the large bowel and rectum) usually causes bright red rectal bleeding.

All GIH when rapid leads to a drop in blood pressure, which can cause light-headedness and loss of consciousness.

How is GIH investigated?

People with significant GIH are usually admitted to hospital. Routine blood tests will be carried out. A cannula will usually be inserted into a vein, and intravenous fluid or blood will be given to replace the lost blood. A urinary catheter may also be inserted.

Most people with GIH will initially be investigated with endoscopy, where a camera on a flexible tube will be inserted into the digestive tract via the mouth or anus. This may allow the bleeding point to be located and treated.

What role does imaging play in GIH?

If endoscopy fails to locate the source of bleeding, radiological investigations are commonly used. CT angiography, where a CT scan is done after injecting contrast (X-ray dye) into an arm vein is increasingly becoming the first-line radiological investigation for GIH.

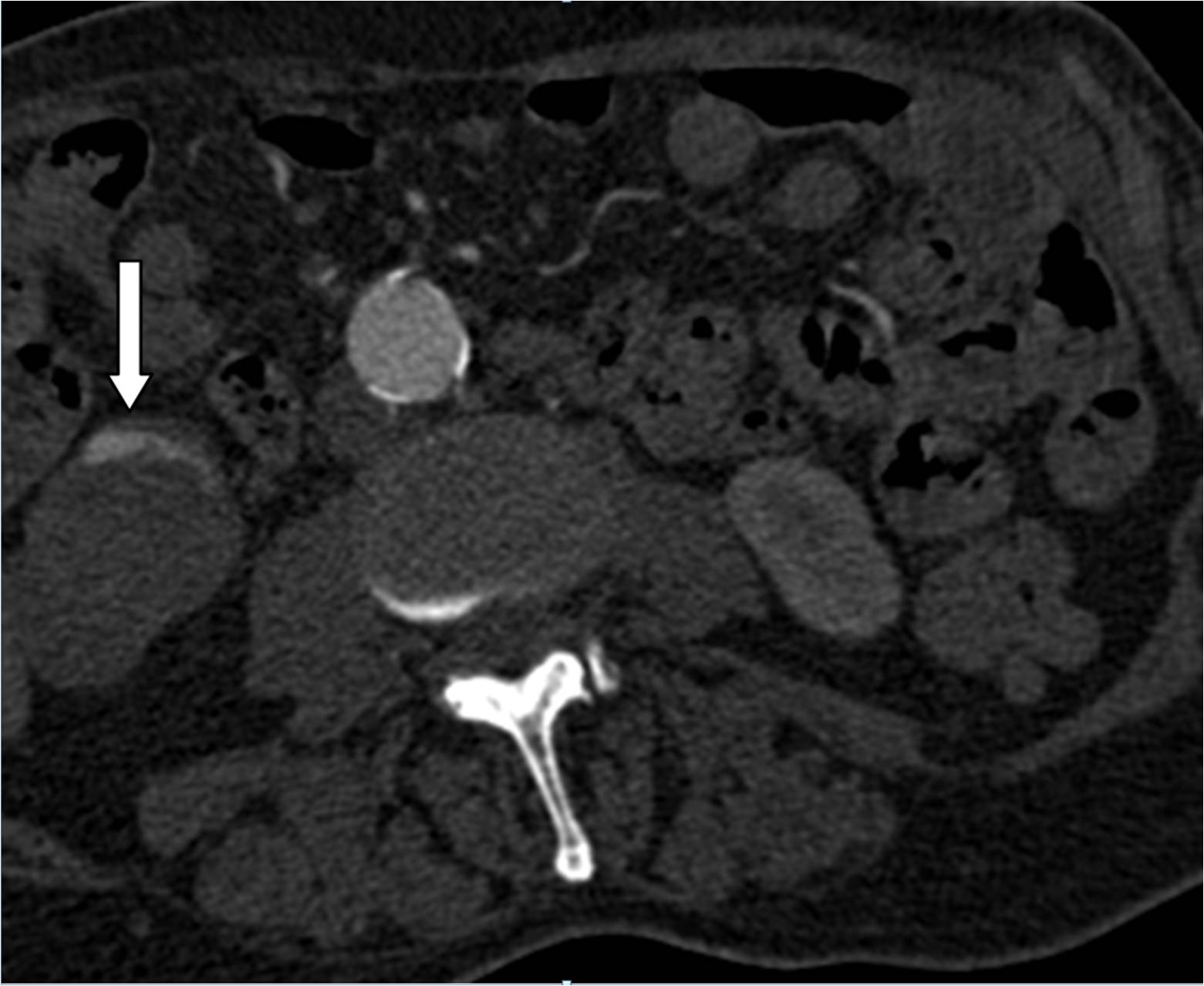

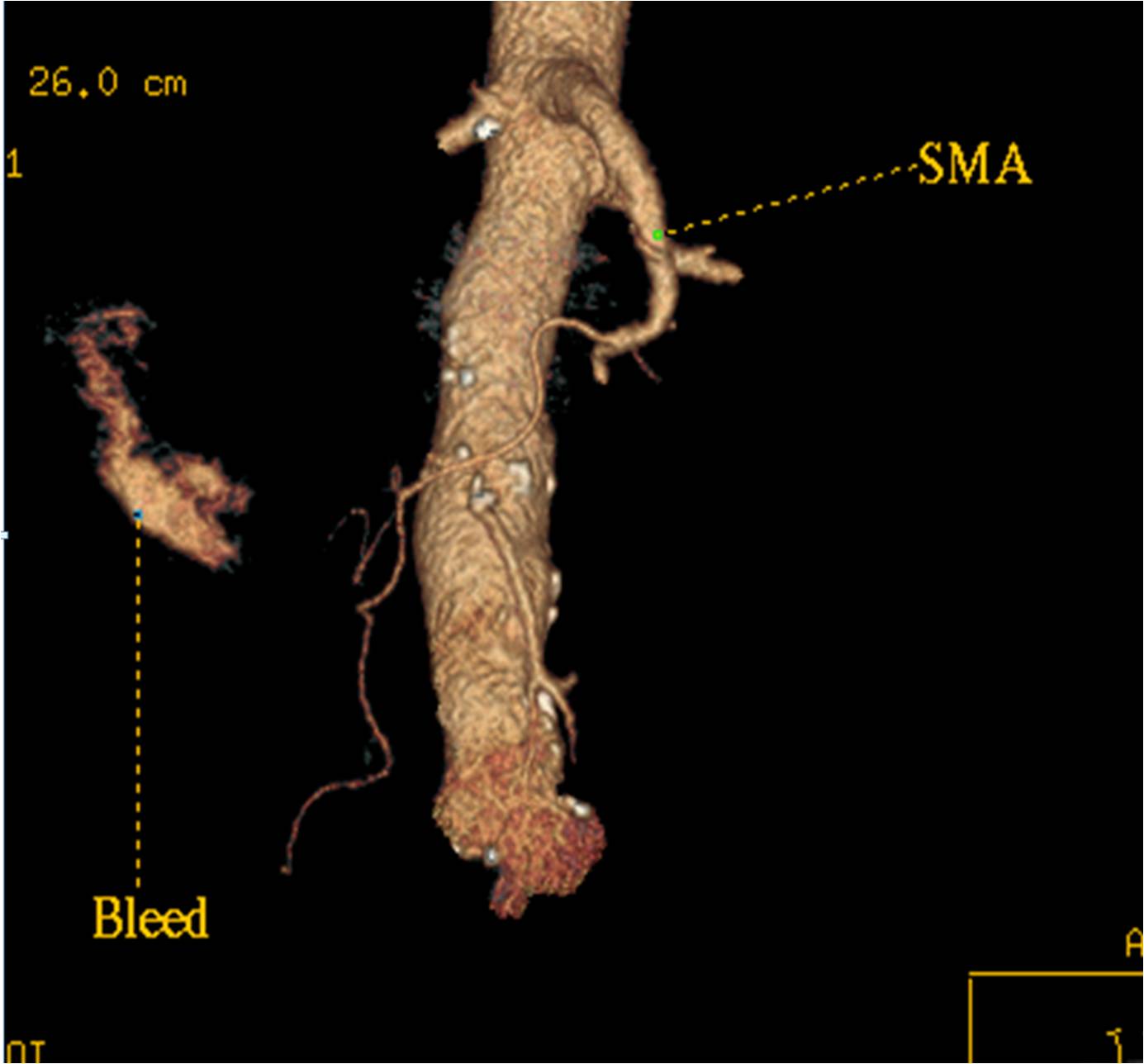

Fig 1. CT angiogram images from a patient with GIH. The white arrow on the first image shows contrast in the large bowel due to bleeding, seen as a white area. The white circle on this image is the aorta, the largest artery in the body that carries blood out of the heart. SMA= superior mesenteric artery, one of the 3 main arteries that supply blood to the digestive tract.

CT angiography is very sensitive, and can detect bleeding at very small rates. However, there needs to be active bleeding at the time of the scan, to allow detection of the bleeding point. This can cause problems with timing the scan, as GIH is often intermittent. Catheter mesenteric angiography (discussed later) also has this limitation. Therefore, these studies may need to be repeated to allow the detection of GIH.

How is GIH treated?

As previously mentioned, it may be possible to treat GIH at endoscopy. Surgical treatment, by removing the segment of bowel suspected to be involved, or by oversewing bleeding ulcers, tend to be used as last resorts. Mesenteric angiography and embolisation is an Interventional Radiological technique very commonly used to treat GIH.

What is mesenteric angiography and embolisation?

This is a procedure performed by Interventional Radiologists to diagnose and treat GIH.

The procedure is usually performed in a dedicated angiographic suite, which has specialised X-ray equipment.

It is performed by accessing the arterial system, usually the femoral artery in the right groin. Local anaesthetic is used to numb the skin. A needle is used to puncture the femoral artery, sometimes using an ultrasound scanner for guidance. A guidewire is threaded through the needle into the artery, and a short plastic tube called a sheath inserted over the guidewire to allow stable access. A variety of preshaped catheters (fine plastic tubes) and guidewires are then passed through the sheath, to allow access into the 3 main arteries arising from the aorta that supply blood to the bowel.

Contrast is injected through the catheter to either detect the bleeding point or to confirm what was seen on a prior CT angiogram. Carbon dioxide gas (C02) is sometimes used as an alternative to contrast. This is safe, and is an established practice.

When the bleeding point is detected, the catheter is advanced close to it. The arteries supplying the bleeding point are then occluded (embolised). This is usually done by deploying small metallic coils of a few millimetres in diameter through the catheter, although alternatively, other embolic agents (eg. tissue glue) may be used. The time taken for the radiologist to find and occlude all the arteries supplying the bleeding point can be variable, due to anatomical differences.

|

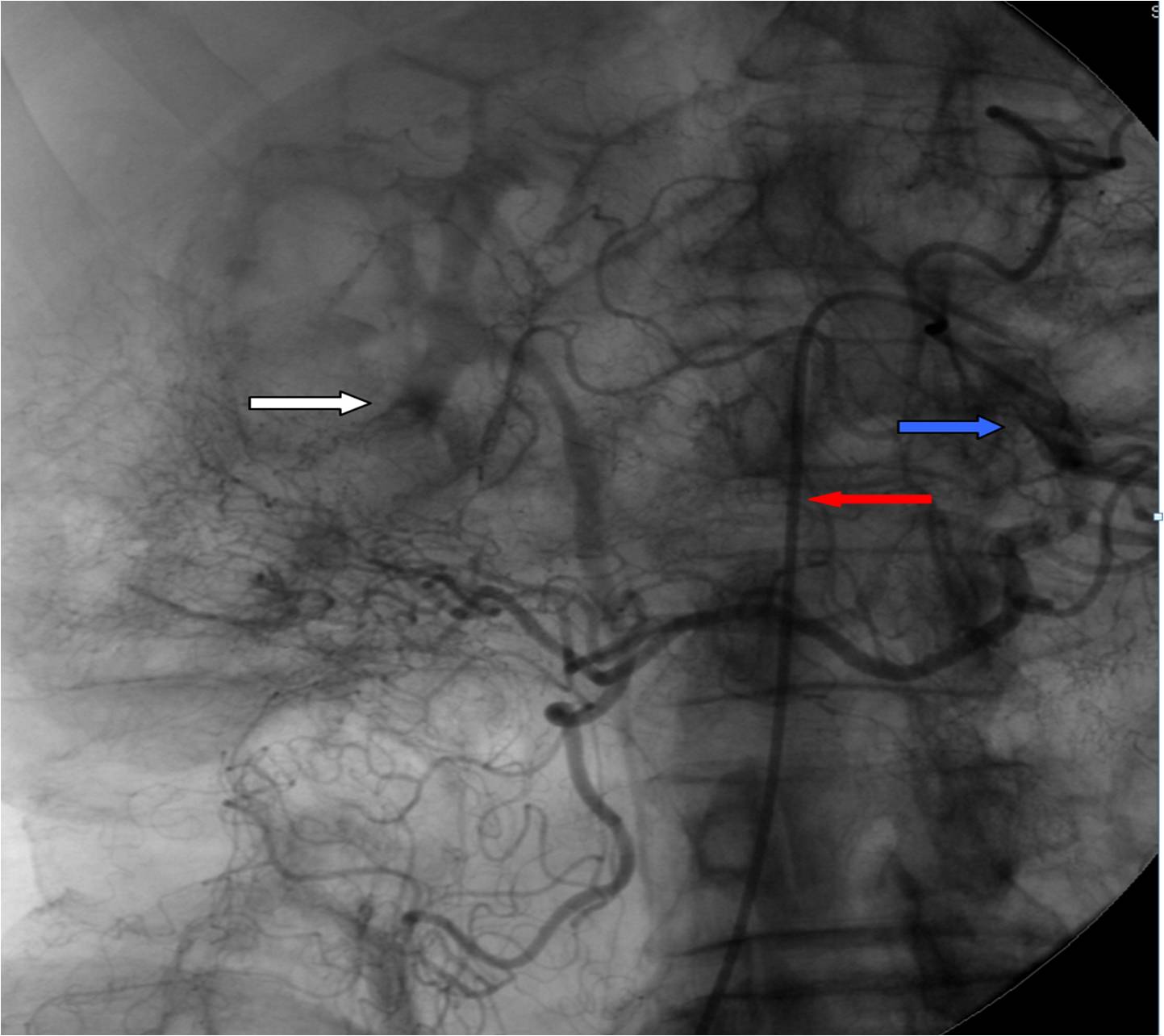

Fig 2. Mesenteric angiographic image from the same patient seen in Fig 1. The white arrow shows a dark area of contrast leaking into the bowel, as seen on the CT scan. The red arrow points to the catheter, which has been passed into the SMA (blue arrow). |

|

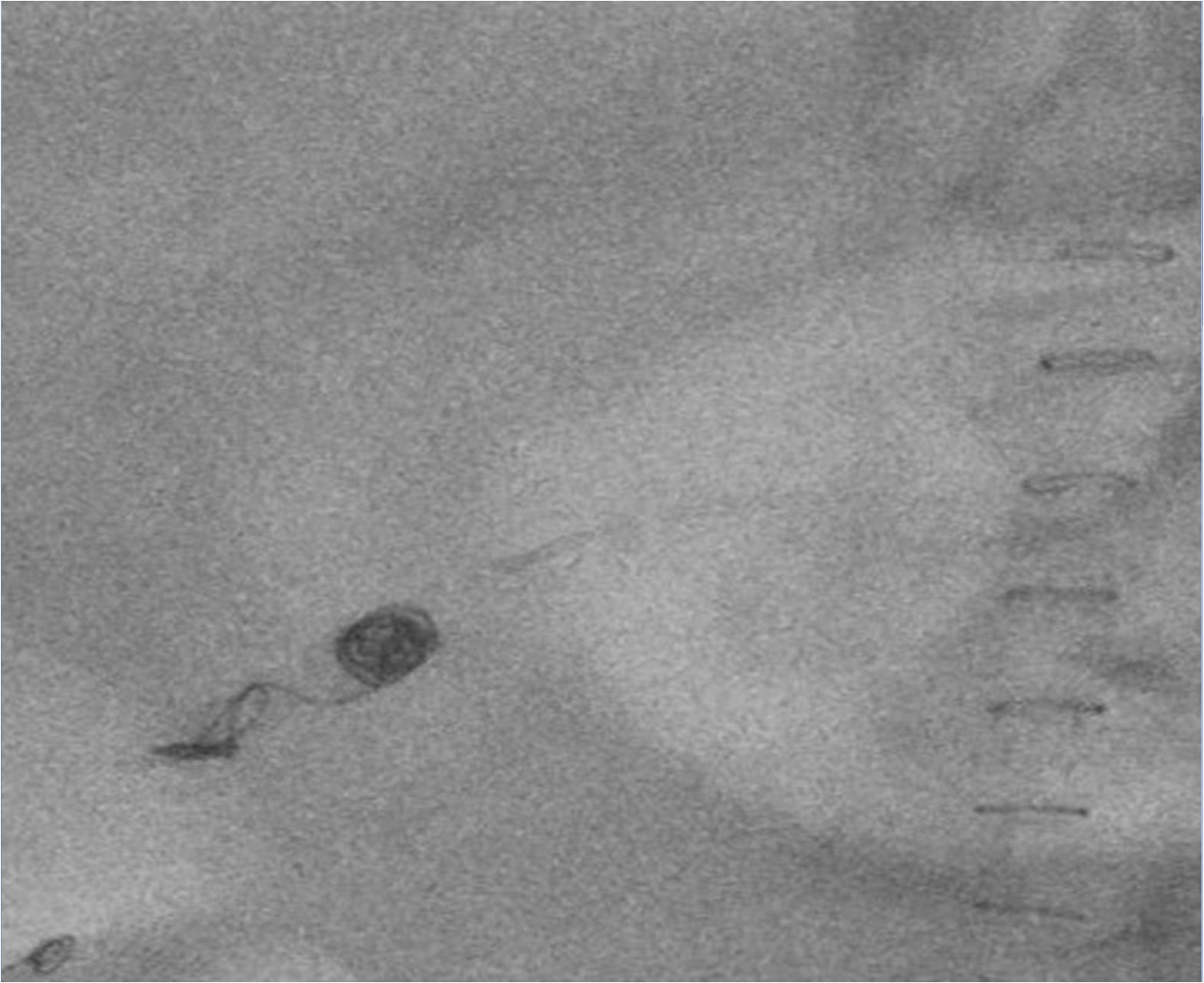

Fig 3. Angiographic image from a different patient, taken after multiple small metallic coils have been deployed to stop GIH. |

What happens afterwards?

Once the procedure is complete, the Interventional Radiologist will remove the catheter, guidewire and sheath by withdrawing them. The puncture site in the artery is then closed, either by applying firm manual pressure, or by using one of a variety of closure devices, which close the hole in the artery with either a stitch, plug or clip.

If there is a risk of further bleeding, the Interventional Radiologist may elect to leave the sheath in the groin, to allow the procedure to be repeated later.

A period of close observation on a ward will usually follow this procedure.

Further tests and/or treatment may be needed once the acute situation settles, depending on the cause of bleeding.

What are the risks of mesenteric angiography?

This is a safe and widely-performed procedure, and complications are rare.

There are similar risks to other types of angiography, which are related to arterial puncture:

- Swelling and bruising of the groin (haematoma)

- Groin bleed

- Damage to arteries, including clot formation (thrombosis) or wall damage (dissection)

- False aneurysm at puncture site

Risks specific to this procedure include:

- Bowel injury due to loss of blood supply after embolisation – this very rarely happens, as the bowel usually gets its blood supply by numerous arterial branches, not all of which will be embolised.

- Damage to other organs due to inadvertent, non-target embolisation – again very unlikely, due to the precise techniques that are used.

What is variceal haemorrhage?

Variceal haemorrhage (VH) is a specific type of GIH that occurs due to bleeding from engorged veins that drain blood from the bowel, usually the oesophagus and stomach. It most commonly occurs in advanced cirrhosis (scarring of the liver), but can also arise due to other, less common conditions.

Endoscopy is often used to diagnose and treat VH.

Transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPSS) is an Interventional Radiological technique used to treat VH. The technique creates an artificial communication between the hepatic portal vein (which drains blood from the engorged veins causing VH), and the hepatic veins, which drain blood into the heart. This relieves the pressure and stops bleeding.

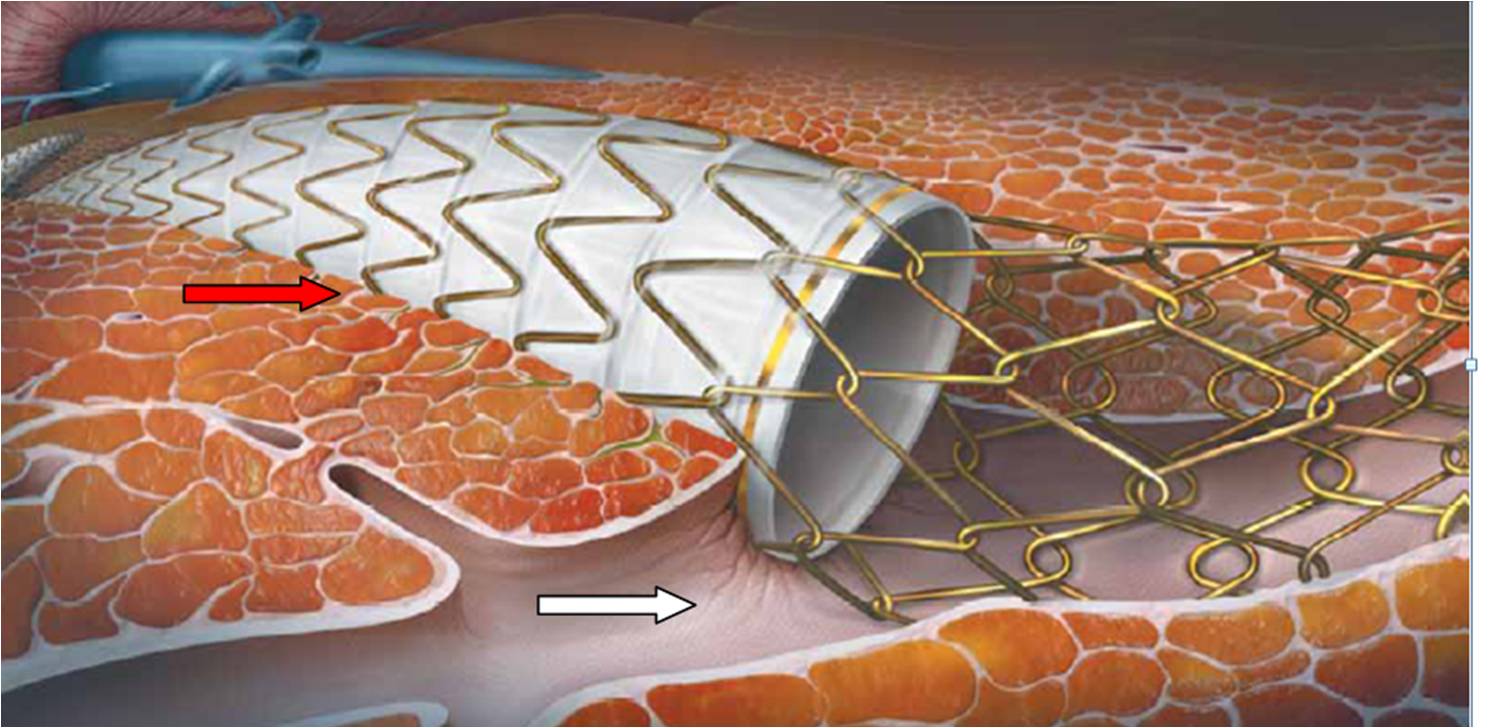

A catheter is usually placed via the groin into the SMA, and contrast is injected. The contrast recirculates into the hepatic portal vein, allowing it to be seen on the X-ray images. A catheter is then passed, nearly always via the right internal jugular vein in the neck into a hepatic vein in the liver. A fine needle is passed through the liver into the hepatic portal vein. This access is used to place a stent (flexible metal mesh tube, in this case usually with a fabric covering), to create the shunt. The bleeding varices can also be embolised at this time.

Fig 4. Angiographic and schematic images of TIPSS. (White arrow = hepatic portal vein, red arrow = stent in liver). Images courtesy of W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc.

In addition to risks associated with all angiographic procedures, specific risks associated with TIPSS include hepatic encephalopathy (neurological symptoms associated with liver failure) and heart failure. This procedure is usually performed in specialised centres for patients who are very unwell.